U.S. immigration enforcement practices have spread to Mexico, resulting in apprehension rates of Central American migrants that rival the U.S. In 2015, deportations of migrants from Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador in Mexico exceeded 165,000, more than twice the number of U.S. deportations to this region. Enforcement-only priorities surrounding immigration policy in Mexico has reinforced oppressive discriminatory treatment toward the indigenous and migrant populations. My work features 26 “stateless” indigenous Mayans who fled Guatemala in the 1980s during a violent military conflict that engulfed the region until the late 1990s, and who fear deportations in Chiapas, Mexico.

Since 2004, I have worked directly with the original Guatemalan refugees and their Mexican born children in the largest refugee settlement – La Gloria – to document their ongoing barriers to political, economic, and cultural incorporation in Mexico. In 2014, indigenous community leaders approached my collaborator, Oscar Gil-García, a Professor at Binghamton University, to assist several residents across three settlements to obtain legal status. In 2014 we petitioned the Mexican government to process the naturalization of residents in La Gloria, San Francisco, and Nueva Libertad (El Colorado) refugee settlement communities. In early 2016, I initiated a photo-documentary project in each community, which involved single portraits of stateless subjects and another with their families.

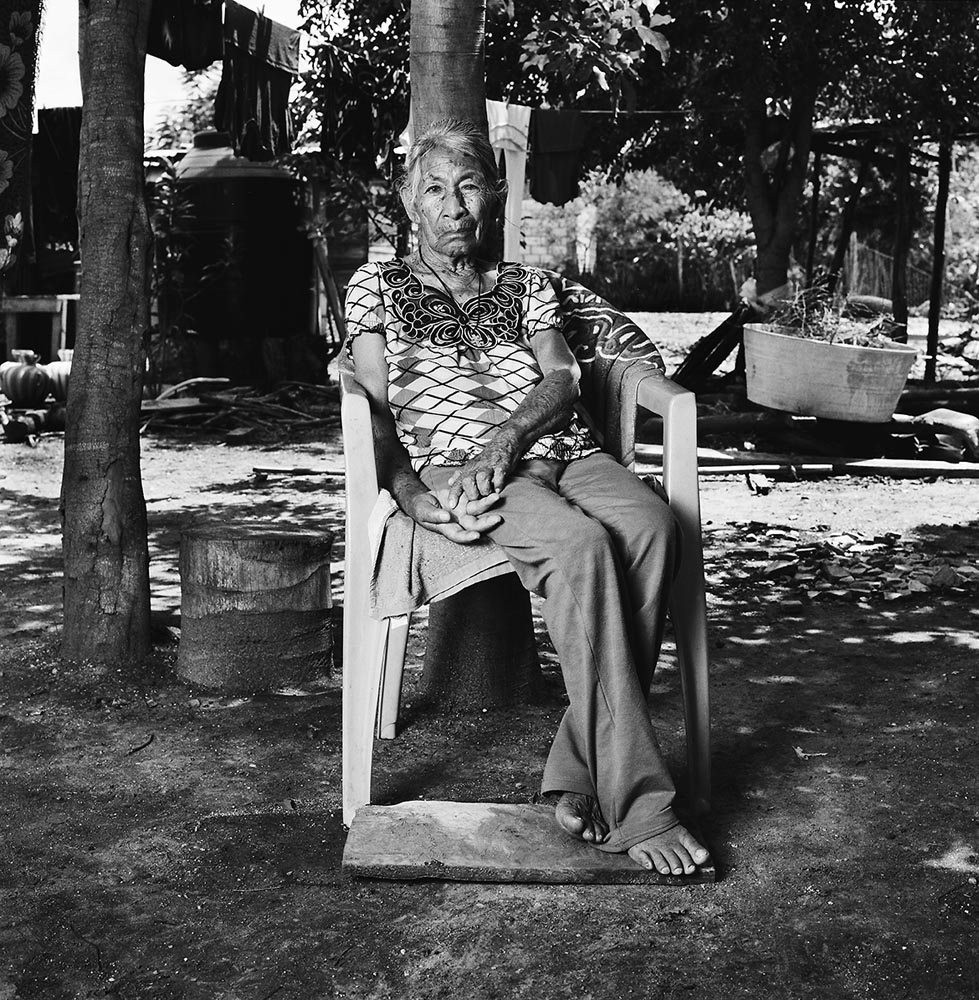

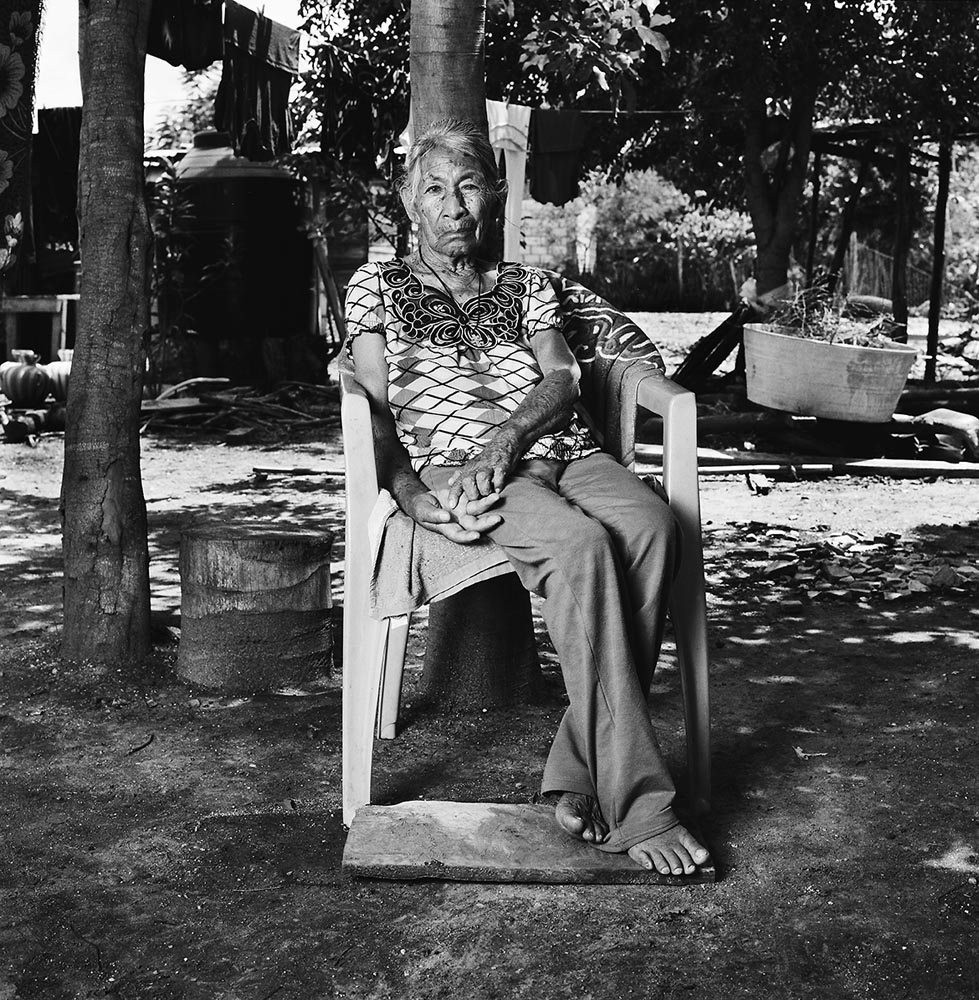

Some of the individuals photographed include: Angél Pascual Francisco – a father of four – who as a child witnessed the slaying of his father, pregnant sister, and 5-year old brother by Guatemalan military forces. This violent event continues to haunt him and shapes his life choices as an adult. María Miguel Pedro (aged 86) is the mother of five and great grandmother to 40 Mexican citizens. A debilitating stroke left her paralyzed and mute in early 2016. Lack of legal status delimits Mária’s access to state covered health insurance, and must rely on her husband to obtain affordable medications to treat her debilitating condition. The family portrait of Amalia Manuel Pedro includes her husband and their U.S. citizen child, Gus, who as a consequence of her 2006 U.S. deportation to Mexico resulted in her husband’s involuntary mobility to Mexico with their son – where he remains in exile. Unfortunately, Gus's experience is not unique – there are more than 500,000 U.S.-born children who as a consequence of a deportation of a family member, are exiled in Mexico. Calls to bolster draconian immigration policies in the U.S. will potentially increase the number of U.S.-born children who, like Gus, are forced to live abroad.

Living in Mexico for over thirty years and raising Mexican and U.S.-born citizens reveals a cruel paradox regarding our subjects’ prolonged statelessness and vulnerability. In many respects these portraits are a reflection of the 9-million mixed-status families in the U.S. Despite a majority of the undocumented migrants having lived for 10 years or more in the U.S., reduced legal options to regularize status, leaves significant family members – documented and undocumented alike – vulnerable to family separations as a consequence of deportations. This oppressive fear was shared by most of the people in my photos. Fortunately, our petition to obtain legal status for all 26 stateless subjects was approved in late 2016. Despite this achievement, tens of thousands who fled military conflict in Guatemala remain stateless throughout the Americas.

The power of my portraits is that they illustrate how despite a protracted denial of legal status in their host society, Guatemalan exiles are able to establish family ties with partners and children – many of whom are Mexican-born citizen nationals. My work also illustrates the profound strength and resilience of stateless subjects’ to support their families and communities, while simultaneously continuing their struggle to gain legal status. Their effort to be recognized as rights bearing members in Mexico mirrors that of millions of unauthorized migrants across the globe who continue to fight to gain a sense of belonging in host nation states, and provides lessons on how immigrant rights can only be obtained through organized struggle against oppression.