DIRECTOR'S CHOICE: Artist's Statement

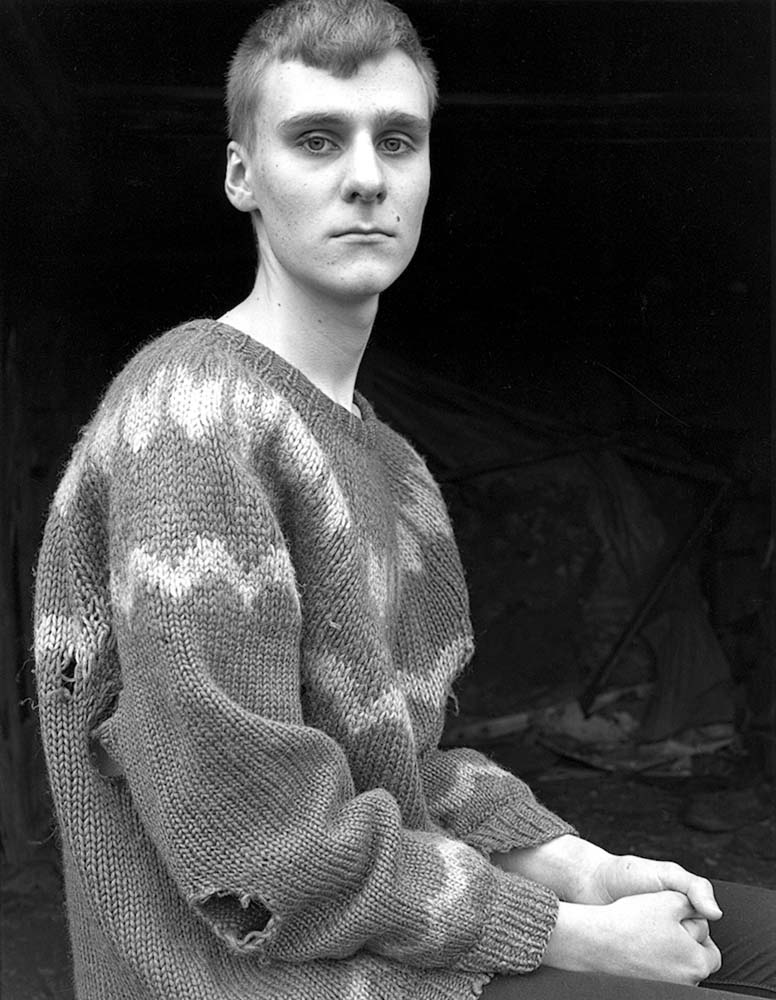

First Place: Agnieszka Sosnowska

A Year Book

I immigrated to Iceland 12 years ago. I teach at a small countryside school comprised of 40 students. I photograph my new life in this remote and rural area of Iceland.

These photographs are comprised of self portraits and of my students. For the past 10 years I have been teaching English to Icelandic students.

As a teacher from another country I have found tolerance, acceptance and caring from this small community of young people.

Immigration has a way of arousing a search for belonging and an image or story can attach one to a place.

DIRECTOR'S CHOICE: Artist's Statement

Second Place: David Gardner

Into the Anthropocene

The dawning of a new Earth Age, the Anthropocene, is the starting point for a new series that seeks to explore vast man-altered landscapes. I traveled to the Palouse grasslands - now wheat fields - of eastern Washington to immerse myself in a landscape terraformed and overlaid by commerce since before the dawn of the Anthropocene (1950 or so, TBD). I wish to bring attention to how global needs impact local landscapes.

DIRECTOR'S CHOICE: Artist's Statement

Third Place: Elizabeth Claffey

Matrilinear

"Matrilinear" addresses embodied memory and its relationship to identity. These images examine family folklore and mnemonic objects passed down through generations of women. The photographs of each object reveal the physical remnants of a body long gone; including stains, tears, and loose thread from clothing that was kept close to the body for comfort and protection. The stitching and/or photographic representations are both a visualization and an expansion of stories shared as family lore. These interruptions also represent the deep influence of one’s familial past on personal identity and perceptions of the body.

DIRECTOR'S CHOICE: Juror's Statement

Kim Sajet

Director, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian

1st Place

A Year Book

These exquisite portraits immediately seemed Icelandic to me—tenderly showing beautiful, stoic people coolly remote from each other set within haunting landscapes of moors and volcanic rock. It isn’t often that a set of photographs convey such a strong sense of place that also speaks to larger universal issues of love, longing, and loss. To quote Henry David Thoreau, “this World seems to be a canvas to our imagination.” I began to think about the differences between The Field Trip and the fabulous The Arrival: Self Portrait with Arnar, showing all the anxieties and longing of youth, in contrast to the stoicism and guardedness of middle age. The series of six images was really well curated, with the photographer building a “collection” of stories we can relate to in our own way. I imagine Alfgerour Playing House, with the sitter clutching her lacy white dress, as a companion work to Fall Harvest: Self-Portrait, where the artist is clutching cabbage stalks, as ways to reveal or hide the female body, both as a promise of pleasure and a return to nature. Similarly, many of the hands are fascinating; tucked under arms to protect emotional vulnerabilities, gripped in the lap to support an open gaze, and clutching the lapels of an oversized suit—less to ward off the cold it would seem, as to perhaps ward off a viewer’s deeper scrutiny.

2nd Place

Into the Anthropocene

This series of landscapes brought to mind Edmund Burke’s “terrible beauty” of nature reference in the mid-eighteenth century when he noted that the terror of natural destruction has a gruesome pleasure attached that is at once awful, exciting, and sublime. The Palouse grasslands—named by fur traders to acknowledge the French word for “lawn”—located in the southeastern region of Washington State, were once part of an extensive prairie that has now become the “bread basket” of American food production. It is one of the most endangered ecosystems in the world. I know this because these photographs, like all great art, encouraged me to delve deeper into the story they are representing. Literally writing this on the first day of the Smithsonian’s Earth Optimism Summit, my wish is that these beautiful/terrible pictures—so carefully balanced in terms of color, composition, pattern and light—help reverse the destruction of the Anthropocene Age and the mass extinctions of plant and animal species, pollution, and climate change, that we have wrought.

3rd Place

Matrilinear

These photographs capture the traces of bodies in well-worn clothes, filled with memories and worn thin through time. The light-box effect of the clothes laid upon the inky black background sets up a yearning that both looks back in time and reminds me of the ghostlike beauty and endurance of the human spirit. I feel nostalgic looking at these baby dresses, bonnets, and embroidered tops for a time when my own children were small and motherhood was still a mystery.

A word to the artists

I honestly believe that art can change the world, and as artists, you lead that change. So when choosing what to create, it’s important to start from your own personal wellspring of emotion and experience and then find a way to convey that to the rest of us. One great picture is worth more than ten, so take time to curate your submissions with an eye to developing a journey for the viewer. Just like each chapter in a book makes a great story, each work of art contributes to make an impactful body of work. Many times I loved someone’s photograph, but one bad picture—or too many—put the entry out of contention.

Similarly, if you want your viewers to identify with you, don’t use long, overwrought, and verbose language to talk about it! So many of the explanations just seemed incomprehensible and/or pretentious. Curators love artists who have a simple and elegant turn of phrase—trust me on this. At my museum we call it “art-speak flapdoodle”!

And finally, ask yourself if what you are presenting will be of interest to someone else in a new and imaginative way? Many of the submissions talk of personal experience, documenting autobiographical people and places that no doubt resonate with family and friends. But do they have a transcendent quality that could appeal to complete strangers sometimes living on the other side of the world? Similarly, are your pictures unique, or are you taking another famous artist’s ideas or style and adapting them with little change? Artistic appropriation, unless it’s extremely sophisticated and “additive” to the original idea, isn’t fair to the person whose work you admire—or, to be honest, yourself.